In the mid 1800s a disease began to infect southern cattle and had the potential to devastate the entire United States cattle industry. It was called tick fever, Texas fever or Texas cattle fever. Other names were Spanish fever, redwater or splenic fever. The comments below represent our best effort to understand the history of this malady and how the treatment developed over the years.

Cattle raisers became aware of the problem as far back as the 1860s, though the cause was a mystery for years afterward. It took several decades before it was isolated as having been caused by a microscopic protozoa called Babesia bigemina and was transmitted to cattle by ticks that the cattle came in contact with in pastures and on cattle drives.

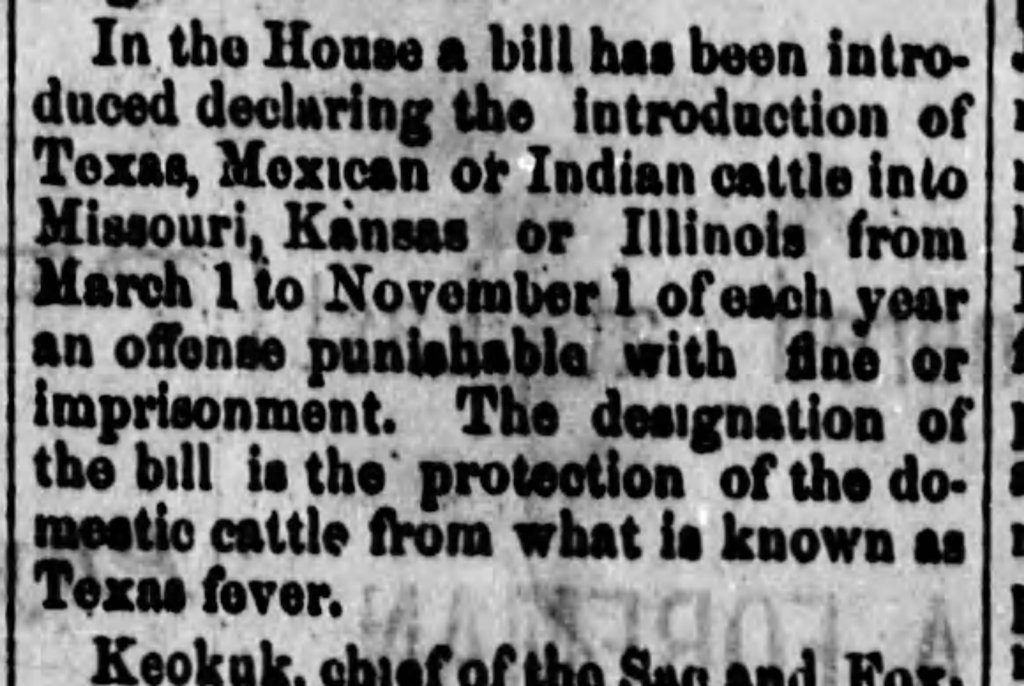

The response of the cattle market states was to quarantine cattle from the South, beginning in the late 1870s. Sometimes even armed riders turned back herds heading to northern markets. The above clipping from 1878 notes that there was a quarantine of cattle after determining that the disease was being carried to market by these animals, though it was suspected years earlier. One puzzling aspect was that the cattle from Texas mostly seemed healthy to all appearances, although it was deadly to other cattle. It was later determined that the Texas cattle, mostly longhorns at that time, could have developed some form of immunity to the disease while all other cattle were vulnerable to it.

The disease was found to be borne by ticks. The female ticks would drop off the animals to lay thousands of eggs. In the life cycle of the tick, the eggs would hatch in pastures after one herd had passed, grow into larvae, develop into ticks which would attach themselves to later herds. It was almost a “perfect” cycle and system of transmission. Some estimates were that ninety percent or more of the infected cattle died within a few days of being exposed. The spreading protozoa caused rapid weight loss, loss of red blood cells, reduction in milk production, muscle tremors, high fever and bloody urine. With the possibility of millions upon millions of ticks given mild weather, it could have had a plague-like outcome on American cattle if the cattle market states had not established their quarantines.

Though the carrier and the system was researched before 1870, it would be more than twenty years before changes started being made to eradicate the pest. Advances in bacteriology after 1900 in Europe and America led to the isolation of the cause to a protozoa the genus of which was later named Babesia, for Romanian bacteriologist Victor Babeș (1854 – 1926), a medical researcher who worked in the field of bacteriology and co-authored what is called the first treatise in the world on the subject. The disease called babesiosis was found to have been spread by several species of ticks.

The disease was finally brought under control by American researchers and cattle raisers developing ways to dip the cattle in vats of liquid and kill the ticks. Over the years, different solutions were tried, including crude oil. The Portersville Evening Recorder, Portersville, California, carried an article on December 18, 1936, relating that cattle that had come into the state through a break in the international fence separating California and Mexico. These animals brought with them “what they called “Southern Cattle Tick Disease” which had come under the authority of the state agriculture department earlier in the year. The article stated, “Prompt steps taken by the department to halt the spread of the disease are believed to have been effective, all infected cattle having been placed under quarantine. The disease is transmitted among cattle by the Texas fever tick. By dipping cattle in an arsenical solution, the ticks are destroyed. Because cattle may be re-infected by young ticks hatched out on the ground, repeated dippings are necessary to assure the health of the animals.”

Research in the United States included mapping out where the infection originated and how it appeared to spread, identifying the areas where it was common and areas where it was less common. It also included theories about how the infected animals might develop immunity, including the suggestion that they were born with some amount of immunity and that they might come into contact with ticks when they were still strong young calves. Perhaps the calves developed sufficient immunity to resist being overwhelmed by the disease as they grew older, though they were still carrying the pathogen. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) was created in 1884. Part of its mission was to regulate movement of livestock between states and insure the safety to consumers of the product.

USDA researchers credited for Texas fever discoveries include Daniel Elmer Salmon, Theobald Smith, Frederick L. Kilbourne and Cooper Curtice. In 1906, the Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program was funded. The arsenical solution first used in dipping was made up of white arsenic, soda and pine tar. The first dipping vat in the state of Texas was built by and credited to King Ranch manager Robert Justus Kleberg. Under the USDA, cattle from outside the state could be immunized by receiving injections of blood from infected animals. Eventually, there were also advances in dipping solutions to increase effectiveness and reduce the use of hazardous materials.

The disease is still a problem in other parts of the world, but the tick eradication program by 1943 had brought babesiosis in cattle down to a manageable level in the United States. It should also be noted that disease babesiosis is not limited to cattle. Also believed to be borne by ticks, the disease is found in other animals such as horses, various species of deer, certain exotic animals, wild animals like raccoons and others. It is also rarely found in humans.

Two agencies currently head up the federal and state response to the disease. The USDA APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program is headquartered in Laredo, Texas. The headquarters of the Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) are located in Austin, Texas.

There is now a Permanent Fever Tick Quarantine Zone that stretches hundreds of miles along the Rio Grande from Armistad Dam to the Gulf of Mexico. The designated permanent quarantine area serves as a buffer zone for tick infestation. The USDA manages the permanent quarantine area and the TAHC deals with premises outside the buffer zone. There are various levels of “premises.” Depending on the degree of suspected tick exposure, different actions are indicated ranging from injections, dipping, spraying and/or vacating the premises. Dipping vat installations are placed throughout the buffer zone and USDA also can provide portable dipping vats as the need arises. Vaccinations are also available. Inspection of herds for the presence of ticks may be done by private veterinarians, USDA or TAHC personnel.

Sources for this article include publications of the United States Department of Agriculture, the Texas Animal Health Commission and others.

© 2024, all rights reserved.